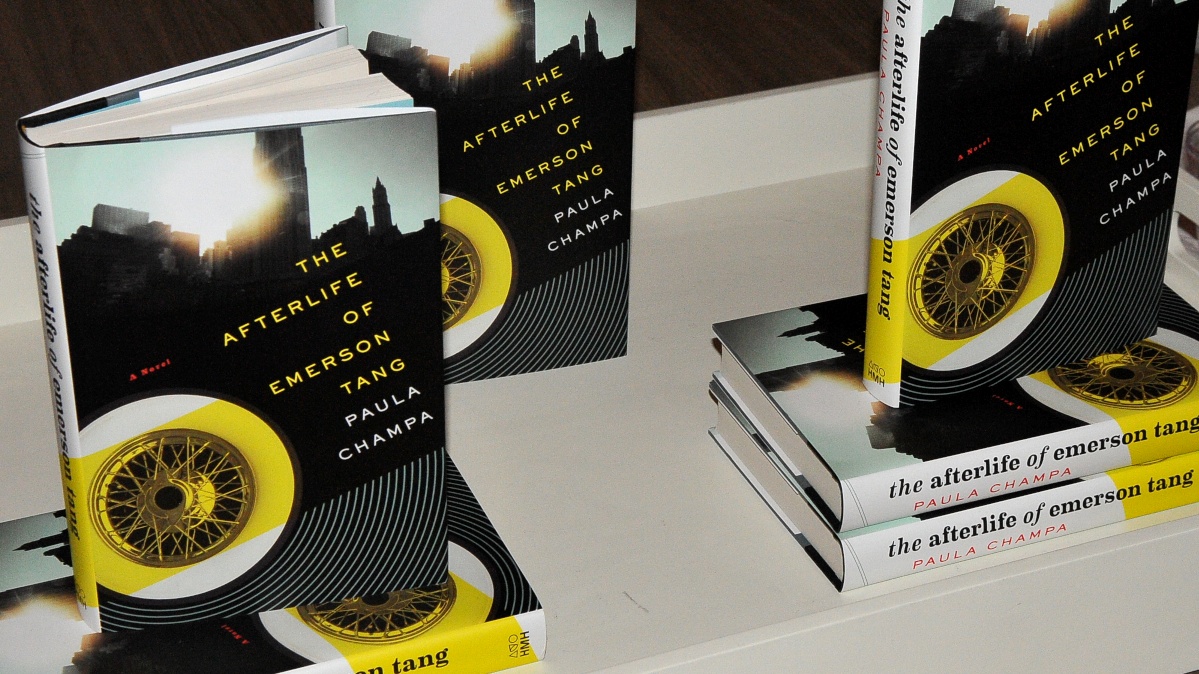

The dimly-lit bar at the West Village’s Jane Hotel in New York City reminds me of what this neighborhood and the adjacent Meat Packing District were like before “Samantha Jones” (from Sex and the City), Soho House and the Apple Store priced out all the fun: tatty, louche, and a great place to indulge your vices. I am here to interview Paula Champa, my longtime friend, journalist and now novelist who I first met in 2003 when we were both living very nearby, she as a contributing editor to magazines including Surface and Intersection while I was a publicist at Mercedes-Benz. We’ve kept in touch over the years despite our many changes of both career and address, and when I learned in March of the release of her first novel – The Afterlife of Emerson Tang – I was eager to read it and feature her here.

The contemporary novel is narrated by Beth Corvid, the companion, nurse and archivist to the title character, a mysterious and wealthy aesthete in the final stages of terminal illness. While readying Tang’s estate for his passing, Beth is approached by Helene Moreau, an acclaimed avante garde artist who seeks to reunite the body of a classic 1954 Beacon – a fictional brand – with its original engine, which she believes to be in Tang’s possession. We soon learn her quest is of particular interest and resonance to Tang, who may seek to thwart Moreau’s success. The author likens the engine’s separation from its body to a disembodied soul, and explores our relationship to the past, grief, and ultimately – closure. As she recounts the faded glory of the shuttered Beacon Motor Company, now poised for a modern reboot with the launch of its first electric vehicle, Champa is perhaps offering a reminder to automakers - and to us all - that escaping obsolescence requires re-imagining the future and relinquishing worn out models of the past.

“In times of mourning, it can feel that you are mostly living with the person who’s died. It’s a very odd feeling of something else driving you other than yourself. ”

When did you begin writing The Afterlife of Emerson Tang?

When I got out of graduate school shortly before the year 2000. I had the general idea for the book and knew it was going to be about grief; but grief is an abstraction, and it’s very difficult to interest people in abstractions. People want to read about characters and stories, so I was looking for a way to ground this abstraction of grief in something concrete. I was reporting on car design when it occurred to me that you could take an engine out of a car and replace it, and the idea that there’s a driving force separable from the thing that it drives was interesting to me. Similarly, in times of mourning, it can feel that you are mostly living with the person who's died. It’s a very odd feeling of something else driving you other than yourself, like having some other engine. It’s forcing the analogy a tiny bit, but it allowed me to build a very concrete scenario where people are missing something in their lives, and looking for something.

The analogy didn’t feel forced at all, and was subtly played. I found the characters so immersive that while cars and the automotive world provide a backdrop for the story, they don’t overrun it.

Thank

you,

I think being an outsider really helped because while I was learning

about what cars were transforming into – including alternative

power-trains and

drive-trains, and new ways of thinking about transportation – I didn’t

have any

context or grounding to know the history of what had come before. So I

was in a sociologist's role,

looking at all of this as an outsider yet caring about it very deeply

because I

found a wonderful community that I really enjoyed spending time with. I

saw how people become

bonded through cars, car clubs and racing, and started feeding more and

more of that culture into my notes. Then to bring more meaning and color

into the book, I started to delve into what cars had meant during the

past century, and why they affected our lives so deeply.

You just touched on the topic of the car community, which tends to be dominated by men. As a woman breaking into car journalism, did you have any hesitations?

If you are going to be a writer or a reporter, you have to have a beginner’s mind and be willing to learn your subject matter. The whole point for me was learning a subject which I knew nothing about. It was intimidating at first but that made me very willing and happy to learn whatever I could. I didn't have any particular ego invested – I was just interested in learning. Every conversation I would find was a challenge to me. How much could I learn? How much of this history can I assimilate or contextualize?

Who was your inspiration for the title character, Emerson Tang?

When I was much younger, I had lost several family members, teachers and a friend who was quite a car buff, but I went out of my way not to use reality. I wanted to create a fictional world that would still ring true emotionally.

“Cars are only a hundred or so years old, and are both in their adolescence and represent adolescence on a couple of different levels.”

www.PaulaChampa.com

It's impressive how you married the very personal topic of grief with cars, a subject matter you knew so little about.

I was curious why as a culture we are dragging our feet when it comes to cars, and I think it has a lot to do with nostalgia, which is closely related to grief. Cars are only a hundred or so years old, and are both in their adolescence and represent adolescence on a couple of different levels. Most of us learn how to drive when we are adolescents, and associate the thrilling feelings of that time of life with cars for good reason – cars are our mode of transport, cars are sexy. Cars and adolescence have been coinciding for such a long time that to have a giant sea change in transportation means turning your back on something that has an extremely strong pull of nostalgia. The current generation of kids – the millennials – really are not that interested in cars and don’t care about them that much. They don’t see them the same way as we did, so I think we might have been the last generation, or close to the last generation, to have that kind of romantic relationship with cars. There are statistics showing that kids are moving back to cities so they don’t have to drive. They can’t afford cars or car insurance, and they like the idea of using public transportation. Likewise students in design programs don’t attach the same romanticism to cars as they are trained to think of the transportation system as a whole.

“If you were growing up in the 50s, a car would be much closer to your life and sense of self than it would be today.”

The deejay’s playing Frank Ocean’s song “Pyramid,” which reminds me of Ocean's recent profile in the New York Times "Sunday Styles" section where he talks at length about his beloved BMW 3-series which he's had since the 90s. I think there are still plenty of younger people, like Ocean, for whom cars are a big part of their lives and their culture.

In any generation I believe there will be people who are drawn to cars, no matter what. My friend has a twelve year-old son who loves supercars, and that still happens, but I am speaking more in a general sense. If you were growing up in the 50s, a car would be much closer to your life and your sense of self than it would be today.

Photography by Nick Ballon

There’s

an argument that kids today have a closer relationship to their computers and technology

than they do to their cars. For example when there's a new iPhone, the hype and excitement is crazy, with kids tracking every step of the technology and each product Apple releases. But you just don't see that sort of rampant enthusiasm for the launch of a new hybrid or electric car. It’s not capturing imaginations in the same way, although I wish it would, and I wish that more was being done in terms of publicity. For example at car shows, it's frustrating when concept cars are moved to the back of the show floor – or their doors are locked and the signage explaining their significance has been taken away – once the press conference is over and the general public is let in.

In your novel, the once-legendary Beacon is readying for a modern relaunch using electric technology. Are you saying that to be respected as a leader in automotive today, a car company must get serious about alternative power-trains?

Someone does have to lead, and I did try to make the point in the book that there has to be a demand, too. I have been speaking to executives from different car companies, asking them why they think we’re having such a difficulty at getting adoption [of alternative power-trains], and I get different answers. Some of them have to do with expense, or people having range fears or anxiety, but it doesn’t answer the larger question: is it only the range or the price difference? Or is there something bigger going on?

Emerson Tang's father makes the point at the end of the novel when he says that if we’re going to be modern, we can’t live like people of the past. So I was actually confronting my own anxieties about progress, especially about technology, because there are a lot of things that we enjoy about technology that move us ahead in a sense, but we lose the romance. I miss the romance of hand-written letters. I still write them, but many people don’t. There are people who are fighting hard to keep books as a bound object that we hand back and forth rather than an electronic signal because there’s a romance to that paper, the binding, the way you store them. So with each jump forward there’s a little bit of anxiety, so I am challenging myself to think more progressively as well.

Please visit www.PaulaChampa.com to learn more about the author and acquire your very own copy of this lovely book!