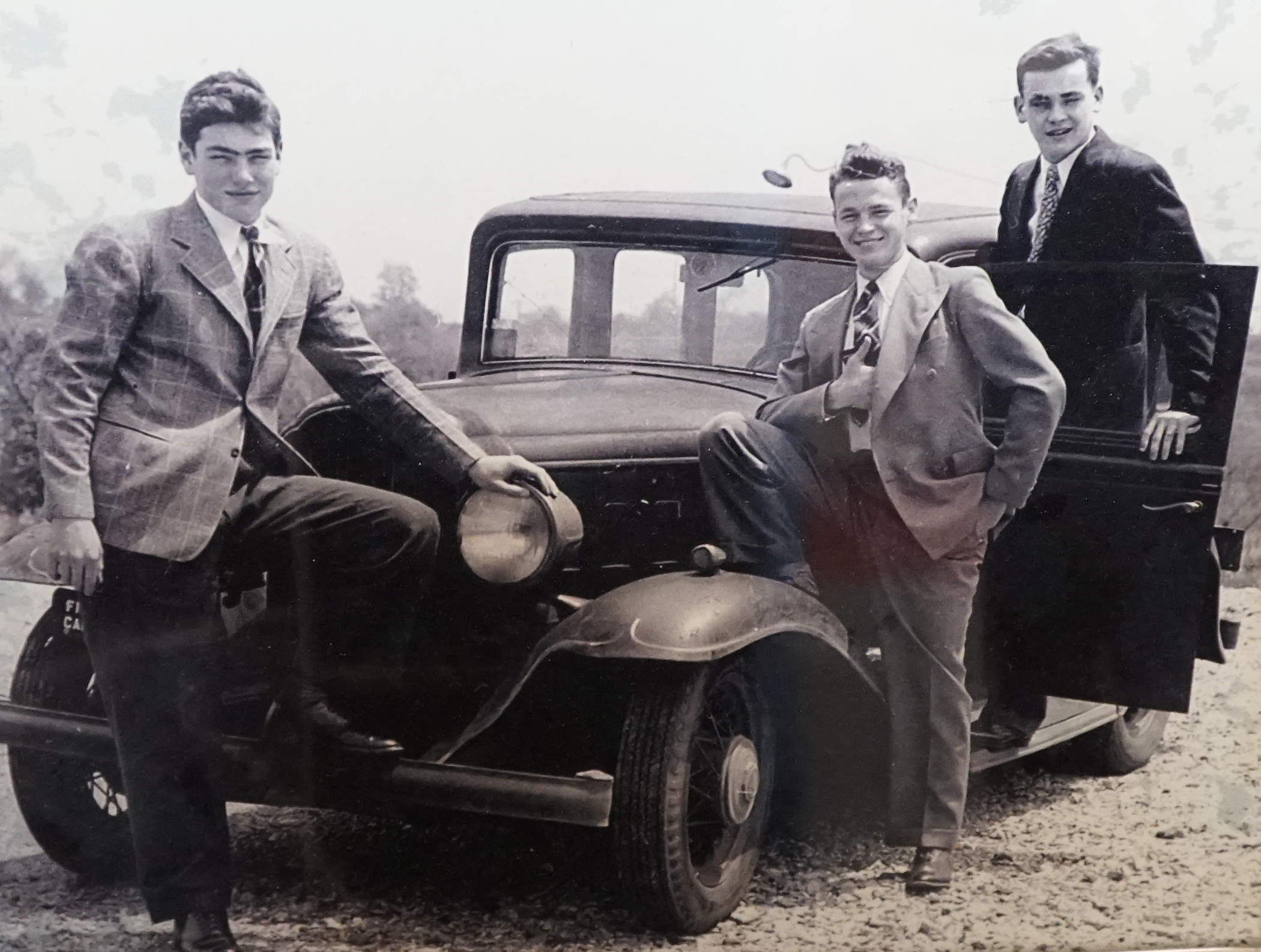

Pitching my stepfather’s obituary to the Wall Street Journal when he (above, far right) died last month was my final act of love, and of duty, to a man who I would like to think shaped my character, and who certainly taught me countless lessons. It’s a testament to his accomplished life that even when 90, retired for twenty-five years and deceased for three days, he still wielded the clout required for the Journal to call me back in a matter of hours, running an article over the weekend. His was a remarkable life built from the humblest of origins and I am happy to report that good guys don’t always finish last.

The journalist writing the obituary asked members of the family to share stories that captured the essence of the man beyond the black and white accomplishments of his remarkable business career, looking for a bit color if you will, to flesh things out. I had a number of stories at the ready, none of which I chose to share once he and I got on the phone, partly because I didn’t want to draw any of the article’s spotlight and also, as a publicist, I know the editorial process and didn’t want my words or sentiments misconstrued – especially not in my stepfather’s obituary in the Wall Street Journal – of all times and indelible places.

Not surprisingly, some of my favorite stories starring my stepfather are closely associated with cars, one including the 1985 Series III Jaguar XJ6 that my mother would drive for many of the years we were living in LA. It was Arctic Blue metallic over an Isis blue leather interior, and it was…everything. My Mom first picked me up in it at school during a heat wave, I’m guessing it was October, as that’s when we reliably had heat waves in LA, and the car was brand spanking new: then 14 years old, I had no idea they were getting a new car, so its arrival – replacing a green Porsche 924 with a two-tone brown and tan leatherette interior – was a complete and sublime surprise. Despite the sweltering heat, I remember how cool, and crisp and expensive it felt inside; the metallic clack of the door locks, chrome clapping chrome as they shut; the vertical expanse of the walnut dashboard; and the whirring, un-fussed surge as we gently pulled away from the school gates. I was not a popular nor particularly happy child, so being whisked away accordingly was heavenly, an escape cocoon, and I knew somehow, in time, I would make this Jaguar…mine. In the weeks that followed, I poured over its owner’s manual, studying the car’s every function, curve and nuance, sitting in its driver’s seat, fiddling with the radio and admiring the emerald green glow of its Smith gauges and square pushbuttons of its digital trip computer until my parents told me I’d kill the battery and, besides, it’s time for bed. But sitting, admiring and fiddling isn’t quite the same as actually having a go, is it?

When my parents would travel, which was very frequently, Ms. Hughes – to whom I once referred in casual conversation with my stepfather as his “secretary, Joyce,” and was sternly corrected to address her respectfully as his Executive Assistant, Ms. Hughes – would compile his agenda, a copy of which was posted in the kitchen so that I and, more importantly, whomever was staying with me while they were away, knew their movements. On this occasion my parents were landing in Van Nuys from Saudi Arabia in late afternoon, so stated the schedule, and my sitter this time, my stepsister, Andrea, had left mid-morning on this fine Sunday, leaving me with six rare, un-chaperoned hours of 14 year-old freedom before they were home. I’d found during my many explorations of the Jaguar’s innards a clip connecting two sets of wires tucked up behind the gauges above the driver’s side foot-well. Might the speedometer – and, more crucially, the telltale odometer – be left inoperable if I were to disconnect the clip? Upon doing so, I started the engine, and just as the rev counter was sleeping soundly, so was too to my delight was the speedometer as I pulled the gorgeous, forbidden Jaguar from the side of the house, turning right out the driveway onto North Palm Drive. With my eyes trained to the odometer for even the slightest act of betrayal, I continued South towards Santa Monica Boulevard and after a few tenths of unregistered miles I determined I was in the clear. Looking back, I simply cannot believe I had the nerve.

At first I loped gingerly around the flats of Beverly Hills running pretend errands. Emboldened by the absence of sirens and flashing lights, I then made a more sporting run up Coldwater Canyon, across Mulholland Drive and back down Beverly Glen. It handles very well for such a large car! Not quite ready to go home nor with anywhere in particular to go, I headed to the Beverly Center mall where, with no money to spend nor credit cards to swipe, I got bored in an hour and was soon lowering Jag’s the electric window, nonchalantly handing my validated parking ticket to the attendant seated in their little glass box, and headed back home.

As I pulled up to the house, a sight in the driveway made my blood run cold; my stepfather’s dark blue Ford LTD Crown Victoria with the landau roof – the company’s previous CEO’s had all opted instead to drive a black Lincoln Continental, but that was not his style – had returned, presumably with them in it. It couldn’t be true, they weren’t due back for hours, and yet there, inexplicably, lay the cold, hard fact that I was in deep, deep shit. Gripped by panic, I devised a desperate plan to give me a fighting chance, bursting through the front door with the pronouncement that I’d just discovered their XJ6 on a side street – less than a block away!! – with its engine running, windows and sunroof open, and radio blaring a station I’d certainly never listen to! It had clearly been taken for a joyride by thugs and thank God I’d found it! My mother looked to me with eyes that had been crying for hours and said, bewildered, “what do you mean the car isn’t here?” They hadn’t noticed it was gone, but were worried as I wasn’t home and hadn’t left a note. My stepfather was very matter of fact with the news, and said, “well, Joe, let’s leave the car right where it is while I call the police so they can investigate and dust for fingerprints, and put whoever did this in jail.” The jig was over, and it was, fair enough, years before they trusted me again.

My stepfather was determined that despite growing up in the flats of Beverly Hills in the 80s I’d not become a character from a Brett Easton Ellis novel. When I was 15 I had lost a bunch of weight – deliberately, through not eating and working out – and he thought I was doing drugs, and didn’t believe me, no wonder why, when I said I was not, and we had a showdown at dinner one night with my insisting to be taken to Cedars Sinai for a drug test or else he drop it for good, which he did. When I was 17, on a break from college, I told my mother I was gay and part of me feared there would be repercussions from him. He called me into his office upstairs at the house, and sat me down.

“Your mother has told me that you shared some news with her, that you’re gay,” he said, as I sat there, speechless, with no idea what he would say next, although I should have been more prepared for what would follow. “Don’t ever let your sexuality be an excuse for not reaching your full potential in life,” he said, and these words defined me, and my relationship with him, and his insistence, his life’s mission, I suppose, that he and everyone he loved were provided with the tools required to “meaningfully contribute to society,” those also being his words.

Years later he told me a story from his youth, when he and his brothers, Jack and Bill, were kids working on an old car, a Ford, I believe. Their grandfather had a repair shop for horse-drawn wagons in their hometown, Cannonsburg, Pennsylvania, in the late 1800s, so I suppose it was a family tradition of sorts. His brothers were bigger and stronger than him, and had put the wheels back on this old car, leaving one for my stepfather, Orie, to finish on his own. As the car headed back down the road, one wheel, Orie’s wheel, promptly fell off. I think he told me this story to show that he, too, had failed once or twice in life, although I never did learn what that second time might have been.